David Barton has lately started sounding like the Institute on the Constitution. Michael Peroutka tells people that the American view is based on the Declaration of Independence and proves that

“The American View” of government is that there is a God, the God of the Bible, our rights come from Him, and the purpose of civil government is to secure our rights.

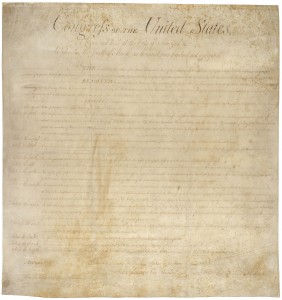

Barton promoted those points on Glenn Beck’s show recently and added that the Bill of Rights came from Genesis 1-8. Watch (from Right Wing Watch):

[youtube]https://youtu.be/g8Z8sWQM3ig[/youtube]

At 1:42 into the clip above, Barton said:

And they held that all those came out of Genesis one through eight and that’s what they looked to, Genesis one through eight. They went through and said here’s the rights we see and that’s why governments exist.

I can’t remember ever hearing Barton cite the part of the Declaration in bold letters below:

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,

Where do the powers come from? The consent of the governed. If the governed want something other than what Barton thinks the Bible teaches, then would Barton say the Declaration is wrong?

As usual Barton isn’t specific about which founders said what. I have pointed out several times on this blog that Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration, did not point to the Bible as a source for the document. Below is a segment from a previous post which cites Jefferson’s description of the influences on him as he wrote the Declaration:

When Jefferson wrote about the Declaration, he did not credit the Bible or Christianity.

First, to Henry Lee on May 8, 1825, Jefferson wrote:

But with respect to our rights, and the acts of the British government contravening those rights, there was but one opinion on this side of the water. All American whigs thought alike on these subjects. When forced, therefore, to resort to arms for redress an appeal to the tribunal of the world was deemed proper for our justification. This was the object of the Declaration of Independence. Not to find out new principles or new arguments never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before: but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take. Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion. All its authority rests then on the harmonizing sentiments of the day, whether expressed in conversation, in letters, printed essays, or in the elementary books of public right as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, &c. The historical documents which you mention as in your possession ought all to be found, and I am persuaded you will find to be corroborative of the facts and principles advanced in that Declaration.

Who wrote the “elementary books of public right?” Moses? The Apostle Paul? No, Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney contributed to the “harmonizing sentiments of the day.” A case could be made that some of that harmonizing sentiment derived from religious sources with religious references, but Jefferson did not mention them or appeal to them as primary influences.

In 1823, Jefferson told James Madison (referring to Lee’s theories about the source of the Declaration):

Richard Henry Lee charged it as copied from Locke’s treatise on government. Otis’s pamphlet I never saw, and whether I had gathered my ideas from reading or reflection, I do not know. I know only that I turned to neither book nor pamphlet while writing it. I did not consider it as any part of my charge to invent new ideas altogether, and to offer no sentiment which had ever been expressed before.

According to Jefferson (and in contrast to what the authors of the Founders’ Bible want you to believe), he did not turn to the Bible when writing the Declaration of Independence. Christian historians Mark Noll, Nathan Hatch, and George Marsden got it right when they wrote in 1989:

Here then is the “historical error”: It is historically inaccurate and anachronistic to confuse, and virtually to equate, the thinking of the Declaration of Independence with a biblical world view, or with Reformation thinking, or with the idea of a Christian nation. (p. 130).

I will add that I can’t see how the Bill of Rights can be found in Genesis 1-8.

What If Genesis 1-8 Was the Source of Our Rights?

It did get me wondering what the Bill of Rights would look like if the founders had used Genesis 1-8.

The first amendment probably would not be the same since everybody would have to observe the Sabbath on the same day. Women would be ruled by men (well, that isn’t so far off from the founding era). Burnt offerings would be a right. Murder would not be a capital offense. As with Cain, a murderer would have the right to be banished with protection from retaliation and the ability to marry. Polygamy would be a right. Nephilim-human marriages would be protected.

I just don’t see anything about quartering soldiers, search and seizures, juries, or trials, etc.

During this clip, Beck asked Barton to bring in the Bible and point out where these things are found. I think that is a super idea that will probably never happen.