On his Facebook page, pundit David Barton has been active in support of Rowan Co. (KY) clerk Kim Davis. Federal judge David Bunning found Davis to be in contempt of his order to issue marriage licenses to all couples, gay and straight, in Rowan County. Davis refused because she does not want her name on any marriage license issued to same-sex couples. KY law appears to require her name to be on the form.

Last week on a video circulated by Glenn Beck, Barton first claimed that Davis was in the right because she was placing God’s law (as he understands it) in a higher position than man’s law. Then on his Wallbuilders’ Facebook page, Barton claimed that Judge David Bunning was not allowed to order Davis to court because such actions by a judge (member of the judiciary) violated the separation of powers. Barton wrote:

Perhaps the single most important issue in the Kim Davis situation (the County Clerk in Rowan County, Kentucky, who was jailed for refusing to issue same-sex marriage licenses) — an issue about which most observers and commentators have been completely silent — is the flagrant violation of the constitutionally-mandated separation of powers.

By way of background, Federal Judge David Bunning ruled that Davis was in contempt of court, which a court can legitimately do. But he then ordered federal marshals enforce his decision and take her into custody, which he cannot do. Federal marshals are part of the Executive Branch, not the Judicial Branch; he has absolutely no authority to order any federal marshal to do anything.

Significantly, the Founders — and thus the Constitution — did not give power to the Judiciary to enforce any of its decisions — they deliberately made it powerless in this regards. They made the Executive Branch alone responsible for enforcement.

As I will show, U.S. law beginning in 1789 directly contradicts Barton’s claims. Federal judges have power to order penalties and one of the prime duties of U.S. Marshals is to enforce court orders.

Barton claims that Davis has been taken into custody in violation of the Constitution. With an ominous tone, he tells us that this is the “single most important issue” in this controversy. Barton cites George Washington and concludes:

So while the Kim Davis travesty continues, perhaps the most dangerous aspect of the entire controversy is that Judge Bunning personally ordered her to jail, thus blatantly violating one of the Constitution’s most important provisions for securing the liberty of the entire people.

It is stunning just how wrong David Barton is.

The power of a federal judge to order penalties for those deemed to be in contempt of court goes back to the Judiciary Act of 1789. The Constitution in Article III established a Supreme Court and gave Congress the authority to establish lower courts. The Judiciary Act of 1789 established the federal court structure and created the role of U.S. Marshal to assist the court in numerous ways, including enforcement of orders. The statute was passed on September 24, 1789 during the first session of the first Congress and signed by President George Washington (see the original law here).

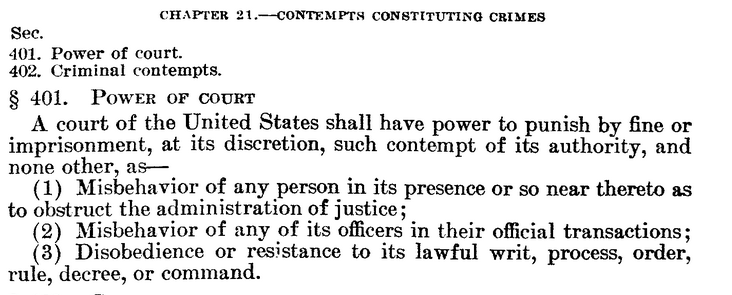

The ability of a court to hold a person in contempt was spelled out in the statute:

The Congress expressly gave federal courts power “to punish by fine or imprisonment, at the discretion of said courts, all contempts of authority in any cause or hearing before the same.” Thus, in a statute passed by Congress (legislative branch), and signed by President George Washington (executive branch), the judiciary was given the power to imprison. There is no separation of powers problem as Barton claims.

Barton then claims that federal judges may not order U.S. Marshals to do anything. However, the Judiciary Act does not support that claim. First, read what the U.S. Marshals’ website says about the historical role of U.S. Marshal:

The offices of U.S. Marshals and Deputy Marshal were created by the first Congress in the Judiciary Act of 1789, the same legislation that established the Federal judicial system. The Marshals were given extensive authority to support the federal courts within their judicial districts and to carry out all lawful orders issued by judges, Congress, or the president.

As a balance to this broad grant of authority, Congress imposed a time limit on the tenure of Marshals, the only office created by the Judiciary Act with an automatic expiration. Marshals were limited to four-year, renewable terms, serving at the pleasure of the president.

Until the mid-20th century, the Marshals hired their own Deputies, often firing the Deputies who had worked for the previous Marshal. Thus, the limitation on the Marshal’s term of office frequently extended to the Deputies as well.

Their primary function was to support the federal courts. The Marshals and their Deputies served the subpoenas, summonses, writs, warrants and other process issued by the courts, made all the arrests and handled all the prisoners. They also disbursed the money. The Marshals paid the fees and expenses of the court clerks, U.S. Attorneys, jurors and witnesses. They rented the courtrooms and jail space and hired the bailiffs, criers, and janitors. In effect, they ensured that the courts functioned smoothly.

Barton says federal marshals cannot be ordered by the judge. However, the Judiciary Act created marshals in order to enforce the work of federal judges (see section 27). Judge Bunning did not violate separation of powers. He relied on a power provided by the legislative and executive branches during the first session of Congress.

The power of a federal judge to imprison has been reinforced in statute in 1831 (chap. 99, sec. 1), 1911 (section 268), and 1948 (chap. 21, sec. 401). The 1948 revision of the statute makes clear the reasons a judge may find a party in contempt.

Mrs. Davis appears to be in contempt of court under #3. In my admittedly limited knowledge, I would say that any attack on the Judge’s action would have to come via a challenge to the lawfulness of Judge Bunning’s order for Davis to issue marriage licenses.

In any case, assuming the order will be affirmed as lawful (and I can’t see any reason it won’t be affirmed), Judge Bunning has the right to imprison her. According to a 2002 revision in the law, Bunning could have fined and imprisoned her.

Barton’s post has been shared nearly 6,300 times. A lot of people are now completely in the dark about the legitimate powers of judges and think incorrectly about the Kim Davis situation. Based on false information, they will argue with their neighbors, and on social media.

Mr. Barton, now what? Shouldn’t you inform your readers?