The Trail of Tears was a low point in American history when the United States government brutally carried out a systematic removal of Native Americans from locations throughout the South to the Indian Territory (now eastern Oklahoma). Broadly the forced removal began in 1830 with the signing of the Indian Removal Act and culminated in the forced death march of the Cherokee in 1838 and 1839 where 4,000 of an estimated 17,000 travelers died. The last Cherokees arrived in present day Oklahoma in March, 1839.

The Trail of Tears has been obscured in the retelling of American history. It seems obvious that the American Family Association does not grasp the significance of the event and has spread misinformation to their millions of listeners and readers about the relationship of the United States and native peoples.

This is not a partisan issue. In 2004, conservative Senator Sam Brownback authored a resolution apologizing to the Cherokee and other native people for the Trail of Tears. It was not passed until 2009 and signed by President Obama on December 19, 2009. According to the American Family Association and Bryan Fischer, the US had nothing to apologize for.

In a small way, I want to remember this sad and regrettable time in our history. We must never forget the consequences of supremacist thinking and pledge, never again.

The first print is called the Shadow of the Owl.

The one below is titled “Trail of Tears” Robert Lindneux, 1942. Granger Collection New York, NY.

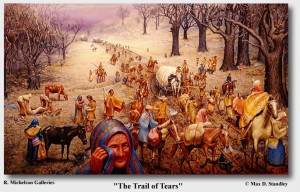

This one is attributed to Max Standley.

I am unable to find the creator of the following stunning portrait.

This article on the CNN website from November, 2010, provides a narrative of the US treatment of Native Americans.

In 1838, Gen. Winfield Scott arrived in Georgia and began rounding up those Cherokees who would not leave willingly. Some 16,000 members of the tribe were herded into makeshift prisons. Scott’s men seized women and children first to guarantee that the men would come out of hiding to protect them.

The Cherokees were then forced into wagons, often at bayonet point. As they left their ancestral land, some saw Georgians digging up family graves, looking for silver jewelry. For five months, they were jolted along the route from Georgia to Oklahoma that became known as the Trail of Tears.

Northern missionaries who shared the ordeal testified to families wrested from their homes so suddenly that they had nothing to protect them against the freezing winter rains. Pneumonia and exhaustion carried off the old and the very young. Although estimates vary about how many did not survive, wagon trains stopped every day for rough burials along the roadside.

As the US apologized to ancestors of indigenous people, I believe the AFA owes them an apology for these recent articles from Bryan Fischer. If Sam Brownback can see the need for reflection and remorse, then surely the AFA can see the need to publicly recant and apologize for this Fischer authored statement:

Had the other indigenous people followed her [Pocahontas] example, their assimilation into what became America could have been seamless and bloodless. Sadly, it was not to be.

What is also sad is the effort to shift the responsibility for the atrocities to those who suffered them.

Other posts on this topic:

Does the AFA agree with Bryan Fischer about Native Americans? – 2/28/11

Native American columnist blasts Bryan Fischer’s “ugly article” – 2/24/11

Bryan Fischer speaks with forked tongue – 2/22/11

AFA divided over Bryan Fischer’s views on Native Americans – 2/14/11

Bryan Fischer explains why the AFA pulled his column on Native Americans – 2/11/11

Native American group: Bryan Fischer’s article “not worth dignifying” – 2/10/11

Bryan Fischer prefers European depravity to the native kind – 2/8/11